6 Metrics That Will Help Improve Your Engineering Productivity

Key Takeaways:

- Choose the right engineering metrics that align and optimize each engineering team’s specific benchmarks and outputs, and reduce inefficiencies

- To measure productivity, sustaining engineering teams should use metrics that compare engineering costs to revenue and deliverables. R&D/NPI teams should use metrics that assess the cost of R&D relative to the value delivered to customers and the potential financial gain for the company

Choosing the Right Engineering Metrics

Engineering metrics are critical to the success of any manufacturing organization. They enable engineering teams to enhance decision-making and measure effectiveness, with the goal of increasing productivity and driving peak performance.

Choosing the right metrics that incentivize good habits and provide meaningful insights can be challenging.

The following process metrics are the ones I used successfully during my tenure at a Fortune 100 Company, where I was responsible for all engineering productivity projects for a 1,200-employee engineering department with an annual budget of $115 million.

The first two metrics measure the productivity of your sustaining engineering team; the next two assess the effectiveness of your research and development (R&D) or new product introduction (NPI) team. These two groups require different engineering metrics because they have different business goals and outputs.

The last two metrics measure the effectiveness of your physical product designs.

Key Engineering Metrics for Sustaining Engineering Team Productivity

The sustaining engineering team is the engineering group that focuses on supporting your current products. These engineers typically deal with design tasks driven by warranty issues, cost-reduction activities, manufacturing support workflows, and engineering custom applications based on your standard product. The following two metrics and manufacturing key performance indicators (KPIs) can assist engineering leaders in learning how to measure, and track overall engineering productivity.

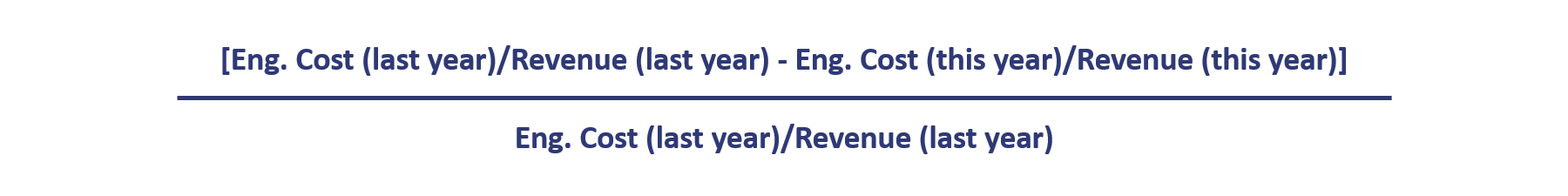

Metric #1: measures the cost of supporting your existing product lines relative to the revenue that such products generate.

Engineering Cost = (Budget or expenditures for the year) minus discretionary spending, (such as R&D and continuing education).

Revenue = Company or division revenue for the applicable year. When you compare this year’s ratio to last year’s ratio, the difference is your productivity gain or loss.

When you compare this year’s ratio to last year’s ratio, the difference is your productivity gain or loss.

So, if your engineering budget (minus discretionary items) was $39 million and your revenues were $780 million, then your engineering cost ratio this year is 5%. If the ratio was 6% last year, your engineering productivity gain was 16.66% [(last year’s ratio)-(this year’s ratio)]/(last year’s ratio) = (6-5)/6.

Why do we subtract discretionary spending? Discretionary spending is subtracted because if you don’t get it out of the measurement from the start, it will be eliminated by management with the intent to reduce cost and make the metric look better.

For example, it is easy for an engineering manager to say, “We are eliminating allocation for all outside training.” Indeed, this will reduce costs, but it will not increase your team’s productivity. In fact, it may hurt it in the long run, potentially creating bottlenecks and reducing lead times.

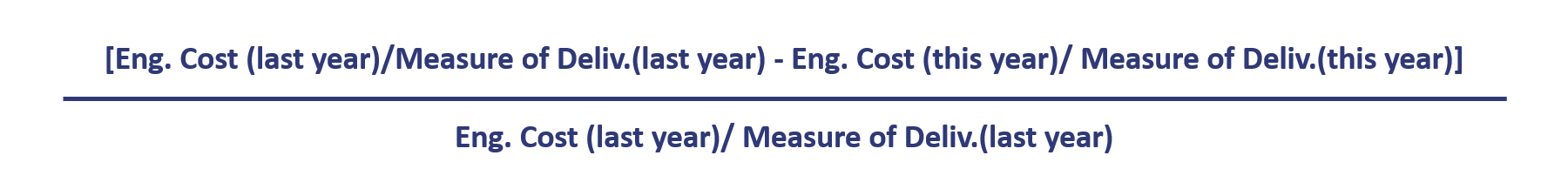

Metric #2: measures the cost of your engineering team relative to what they accomplish.

Engineering Cost = (Budget or expenditures for the year) minus discretionary spending (such as R&D and continuing education).

Measure of Deliverables = Number of unique projects or quantity of items sold.

Again, compare this year’s ratio to last year’s ratio to determine your productivity gain or loss.

For example, if you make custom valves for the oil and gas industry, and last year you sold one project to Exxon Mobile containing 5 valves at a particular flow and pressure, then 2 projects to Shell each with 4 valves, but at a different flow for each project, you sold 3 projects with unique conditions OR you sold 13 valves that engineering had to support.

If your engineering budget was $39 million, your engineering cost per “engineered” project would be $13 million, or your engineering cost per valve delivered would be $3 million. Again, you compare this to last year’s number to see if you are improving.

I recommend the “per unique project method” if you offer mainly custom equipment and the “per item per methodology” if you make more standard or off-the-shelf equipment or components.

Engineering team members may argue that they have no control over revenues or sales. However, they do impact the success of the product in the marketplace. So, this correlation between engineering teams and revenue/sales should not be so easily dismissed.

For companies without two distinct engineering teams, you have to estimate the portion of expenditures dedicated to NPI and subtract that from the total. We will identify R&D/NPI productivity metrics next.

Engineering Metrics Measuring R&D/NPI Productivity

R&D is often considered discretionary spending since a company might forgo innovation and focus solely on its current product line. I have known companies that have done so for several years in a row. However, for companies that have a robust R&D/NPI practice, this expense, even if discretionary, can be significant. Moreover, companies struggle to figure out if they are truly productive in their NPI organizations.

NOTE: The following two engineering metrics use R&D/NPI costs as the basis for the metric. R&D/NPI costs are the cost of conducting the development process. Costs include items like engineers’ salaries and benefits, testing costs, and any outside expert consulting used to support that development project or initiative.

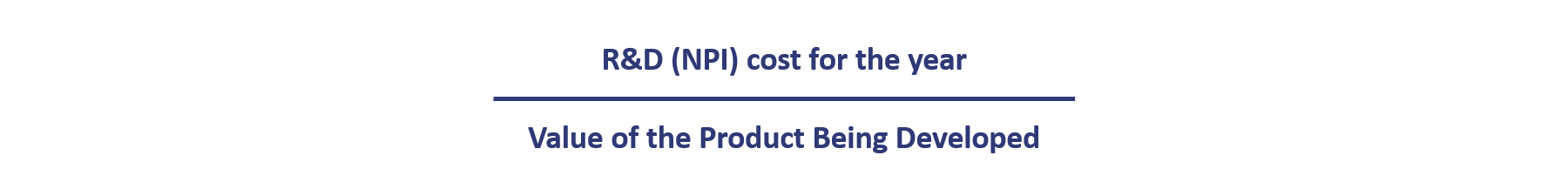

Metric #3: measures the cost of R&D relative to the value that the new design is expected to deliver to your customers.

Consider how your customers or end users leverage your products and their value. For example, if you develop electric motors, your customers most likely value your product by the number of kilowatts your motor puts out. In this case, the metric would be R&D cost/kilowatt (kW) output of the motor or motors being developed; if you make a compressor, it would be R&D cost/CFM*Pressure rating of the compressor being developed.

Think about developing a compressor family with the same basic frame and similar rotating components. However, it provides different behavior at different rotating speeds, so you design with a falter peak efficiency curve. In this case, you get several compressors with just a little more effort than if you developed just one. Hence, your R&D productivity goes up (you would divide the cost by the number of compressors in the family).

You can also use it to track metrics for components. If the R&D project is focused on just a section of the product, a new stator for the motor for example, then the kW output is multiplied by the fraction of the total cost of the product that section represents.

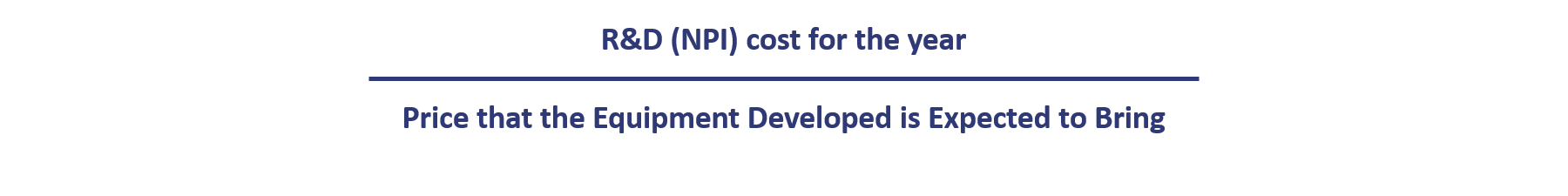

Metric #4: measures the cost of your R&D effort relative to the potential financial gain it will bring to your company.

For example, you are developing compressors. You expect each compressor will sell for $500,000. Your R&D team spent $20 million developing that compressor line. You have an R&D price productivity of 40.

It means that you have to sell X number of units (40 in this case) to cover the R&D cost. Obviously, the lower the better. You can compare this to your sales growth plan for that product. Note when X number of units are expected to be sold and compare that to prior R&D projects to see if the payback period is better or worse.

NOTE: This is not a real payback period. In order for it to be, you would need to know your profit margin. However, at the time you are taking this measurement, predicting the margin is difficult at best. This will be more of a post-R&D metric based on hitting cost targets. Additionally, for some long development cycle times, lasting years, these engineering metrics can still be used by scaling the denominators by the estimated percentage complete on any particular fiscal year.

Measuring the Cost Effectiveness of R&D (NPI) Designs: Are Your Components Cost Optimized?

We have talked about the productivity measurements that will help gauge engineering team performance and drive decisions that will make your team more effective. Now, let’s focus on two engineering metrics for measuring the cost-effectiveness of R&D (NPI) designs.

The reason I am focusing on R&D designs is because measuring potential savings of an existing product’s redesigns or iterations is easy. Take the current cost and subtract the expected new cost. The difference is your expected savings from your redesign engineering process or efforts.

With an R&D (NPI) project, there is no current cost because it’s a new part. How do you know whether or not your design is cost-effective?

In those cases, a frequent rule of thumb to gauge cost-effectiveness is to compare it to a similar part with a similar function that is about the same size on another project. The comparison can determine the cost-effectiveness. However, this method just eyeballs it, making quantification of cost-effectiveness difficult.

Additionally, engineers and development teams should have the freedom to generate greenfield designs, in which case a new part may look nothing like the old part.

In this case, the following two key metrics can be used simultaneously to measure the cost-effectiveness of your R&D (NPI) designs.

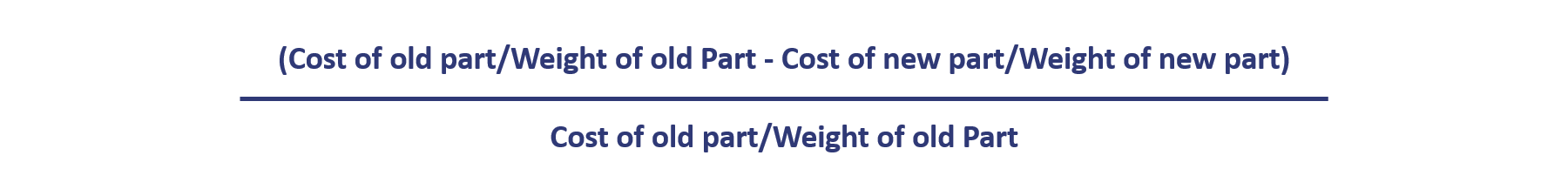

Metric #5: measures the cost effectiveness of a new component relative to a similar measure for a prior component that served the same function.

The designs need not be similar. However, they must serve the same purpose to be a fair measurement.

Using a full-function, real-time cost estimating tool, you can obtain a cost estimate of your part or functional sub-assembly before you make it. Once you have this estimate, divide by the weight of the part or sub-assembly. Compare this ratio to the average of prior similar class designs and see if is higher or lower. If the ratio is higher, then your design is less effective.

For example, you are designing the turbine section for a turbocharger intended for a 1.4 liter engine. The smallest turbo your company has is one for a 2.0 liter engine. You don’t have a “similar” cost for comparison to see if you are in a reasonable cost vicinity. How do you determine cost-effectiveness?

Using your cost estimating tool, you predict the cost of your new intended design for the turbine section of the 1.4 liter turbo is $100. The weight is 5 lbs., so your cost-to-weight ratio is 20.

By contrast, the same sub-assembly weighs 8 lbs. for the 2.0 liter engine. When you estimate the cost of turbine section for the 2.0 liter engine turbo, using the same cost estimating tool, it turns out to be $120.Then the cost-to-weight ratio is 15 (Cost-effectiveness = (15-20)/15 = – 33%).

In this case, your new design is NOT as cost-effective as your current design. Perhaps there is more design work to be done.

Of course, this breaks down if you are designing products with a particular emphasis on weight. If you design aircraft, for example, you are constantly lowering weight. You may want to pay more for less weight, which then turns this metric on its head. If this is the case, you should use the next metric.

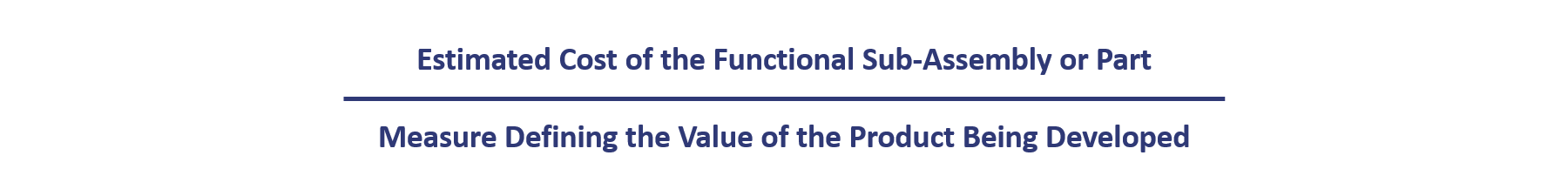

Metric #6: measures the cost of your new component relative to its value to the market regardless of its physical qualities.

Simple designs are rewarded by this engineering metric.

What do you do in the instance where you want to eliminate weight, and are willing to pay more for a lighter component? Measure the cost of your new component relative to the value that it brings to the market. Then compare that to older designs. This process is similar to Metric 3 above.

For example, let’s say you are developing an auxiliary power unit (APU) for an aircraft. You measure the predicted cost of the APU (the product cost this time, not the development cost) and divide that by the power output of the APU in kilowatts (kW) (because that’s how your customers will value that product) to get the cost/kW.

Then take that ratio and compare it to the ratio of prior APU designs to see whether or not you are improving.

This important metric works for both components and entire products with potential new features. I want to make this point because companies usually do not design a whole new product. They are re-designing a component of it to make it better, more efficient, or improve upon it in some other way.

R&D efforts are often geared toward a portion of the product, not the whole product. But you can use this metric on an entire product or portions of the product, comparing it with prior designs to see if your cost-effectiveness is getting better or worse.

For example, you are developing a 70 kW APU, and the predicted cost (using your automation-driven cost estimating tool) of the support frame is $700.t Then your frame cost per kW is $10. You then calculate your existing 90 kW unit and 45 kW unit support frame cost per kW of $11/kW and $15/kW, respectively. This gives you an average of $13/kW for your existing designs. Therefore, your new design at $10/kW is an improvement.

Some companies may prefer to use the lowest $/kW ratio rather than the average for comparison. In this particular case, the new design is still an improvement.

Summary: Leveraging Engineering Metrics

Although not all-encompassing, a sub-set of these six engineering metrics can be used in most industries and across most products to give you the visibility you need to drive your engineering organization to continuous improvement and agile, peak performance, and more effectively meet stakeholder objectives.

Use these engineering metrics as actionable insights but also to help your sustaining and R&D (NPI) engineering teams make better design decisions every day and quantify their success.

Achieve Immediate Cost Savings Without Sacrificing Long-Term Growth

Our Cost Transformation Strategic Report Shows You How